For those who live on Lake Superior, November is a bad time to be on a boat. For well over a century people have told stories, sung songs and searched for ships lost on the lake with the most famous of these ships being no doubt the SS Edmund Fitzgerald which sank on November 10th, 1975 with the loss of her entire twenty-nine man crew. However, years earlier in 1918, another disaster occurred that led to an even greater loss of life, the tragic loss of the french navy minesweepers the Cerisoles and the Inkerman.

As the First World War reached its end in 1918, the allied powers were left to both rebuild and clear the battlefields of the last four years of war. While most historical attention has been focused on the fields of northern France and how even today the clean up isn’t completely finished to the point that there are still people who fall victim to buried shells. The high seas were another area that dneeded to be cleared of dangers. Throughout the war both the Allied and Central Powers filled the English Channel with sea mines. This action, while serving as a way to both protect and attack shipping during the war was now a danger in the upcoming peacetime. In order to sweep the channel the French government ordered minesweepers built to do the job and twelve of these small warships would be built in the Lakehead area at the Canadian Car and Foundry (now Bombardier) facility in Fort William.

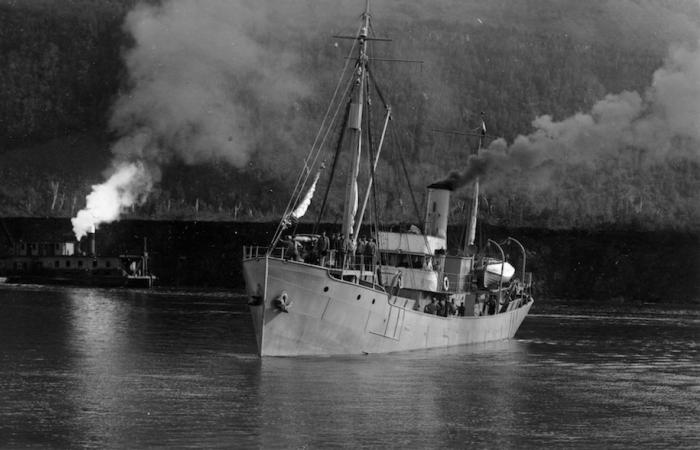

Can-Car built the twelve ships that would become known as the Navarin Class in groups of three, launching them into the Kaministiquia River. They’d be outfitted, then sent to Montreal where after all twelve ships gathered they’d sail to France together. An interesting feature of these ships was that once their duty as minesweepers was complete they were designed to be easily converted into fishing ships for civilian use post war thus potentially giving them a second life.

The last three ships launched were the Cerisoles on September 25th, 1918, the Sebastopol on September 30th and the Inkerman on October 3rd. These ships were all named after battles during the 1854 Crimean War where France and Britain fought against Imperial Russia. By November all three of the ships had been tested and crewed, with each ship having a crew of around thirty-eight French nationals and a Canadian pilot to guide them through the Great Lakes and at around noon on November 23rd, the three ships left the Lakehead bound for Montreal and then to France. They left in November as the crews wanted to get to Montreal before the locks closed or ice blocked their path.

It should be said that while in many retellings of this story, locals warned the crews not to leave in November. I haven’t been able to find solid evidence to prove this part of the story. However, seeing as even in 1918 November’s reputation on Lake Superior was already well established; I would not be surprised if there was some truth to this story.

According to later reports there was some disagreement, as the Canadian pilots wanted to take the more common route along the coast to reach Sault Ste. Marie. However, they were overruled by the overall commander of the three ships, Marcel Adrien Jean Leclerc, a fourteen year veteran of the French Navy who wanted to take a straight path to Sault Ste. Marie. This would prove to be fatal however, as at around 7:00pm that evening a storm began forcing the three ships to head south, seeking shelter near Copper Bay at a place called Bete Grise Bay.

At around 1:00am in the morning the Sebastopol lost sight of the Cerisoles and the inkerman, marking the last time anyone would see the two ships or their crews totalling seventy-nine men alive.

The Sebastopol managed to survive after taking heavy damage and eventually made it to Montreal alone, although Leclerc refused to believe the ships had been lost for days after the disaster saying that the other ships were just ahead or just behind him until he reached Kingston where a telegram reporting the disappearance of the two ships made him realize the truth. He personally returned to Sault Ste. Marie to help with the search.

Official investigations would follow in the years following the disaster which involved at one point Leclerc calling the Canadian pilots “a timid lot” with some taking this as Leclerc trying to blame the Canadian pilots for the loss of his ships. Searches by both Canadian and American ships failed to find any real evidence of the two ship’s fate but it was quickly assumed that both vessels were lost with all seventy-nine souls aboard.

In the end, this tragedy proved to be the only noteworthy event of the ill-fated Navarin Class, as the war ended before the remaining ten ships could leave for France. None of the ships ever got to serve in the role they’d been designed for, ending up sold as war surplus with most becoming fishing boats.

While there have been many attempts since to locate the Cerisoles and the inkerman and various artifacts have washed up over time, like so many other ships in Lake Superior their exact fate and resting place remain a mystery.

I’d like to give special thanks to Brian Berringer who showed me around the location where the ships mentioned in this article were built and gave me some great information about both the ships and our city’s history.