As the 1880s approached, people of the Lakehead knew the fur trade, the industry which had sustained them for two centuries, was winding down. Times were changing. The national railway, the CPR, was making its way eastward and from the west. A ribbon of steel would forge a link to unite Canada from the Atlantic to Pacific. The CPR made the Lakehead its western terminus, and with the railway, new opportunities for prosperity would emerge. The future looked very bright for the citizens of Port Arthur and Fort William. Mining, forestry and grain became the dominant industries. The land was rich with minerals and the forests were vast. Grain transported by rail from the prairies was loaded onto boats to be shipped from Port Arthur, via the St. Lawrence Seaway, to ports the world over. A concern now arose, that with the growth of shipping, the shoreline and the supporting buildings along it needed the protection of a breakwater (break wall). It was held that a breakwater was essential for the growth and progress of shipping.

A monumental task

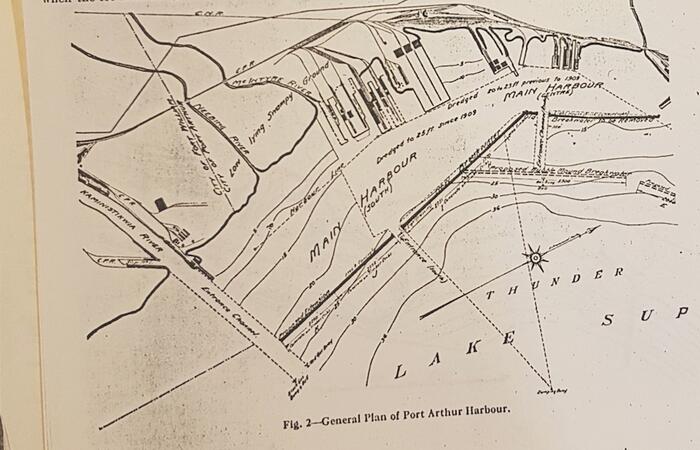

By 1881, plans were well under way to build the breakwater. It was a monumental task that would take years to plan and construct. The Engineering Institute of Canada studied the wave action in the bay and the scouring effects the winter ice would have on the breakwater. They decided that the rubble mound design would be best suited for the harbour conditions. The breakwater would be located one-half mile from shore in a depth of water varying from 24 to 32 feet. It would stand at a level height of 8.5 feet above the water, be 30 feet wide at the water line and 14 feet wide at the top. When complete, the breakwater would continue 2.3 miles from Bare Point south to the mouth of the Kaministiquia River protecting 130 acres of harbour shoreline. Two entrances 370 feet wide, dividing the breakwater into north, central and south sections, would allow for shipping traffic though it. Work began in 1883 to build the breakwater from Bare Point south and from the Kam north. Construction continued year round until 1956. The initial sections of breakwater cost $91.00 a foot to build, but as the years passed, the cost per foot gradually increased to $290.00.

The Institute Engineers decided that the Port Arthur harbour breakwater would be constructed with a crib work of hand-hewn local timber filled with stone. The stone was quarried at what is now the Silver Harbour Conservation Area, loaded onto barges and towed to the construction sites. An exhibit in the Peter McKellar Gallery at the Thunder Bay Historical Museum displays a deep sea diver’s suit used by workers during the construction of the breakwater.

For many decades, the harbour has been an economic life line for the City of Thunder Bay. At one time, the Port of Thunder Bay was heart of Canada’s grain trade and was the largest grain handling port in the world. In addition to grain, the Port of Thunder Bay has shipped a wide variety of commodities such as coal, lumber and iron ore just to name a few.

Nearly a century and a half after building of the breakwater began, or rather the break wall as we call it, little of it still remains as it was originally constructed. Restructuring of the wall with the latest designs, repairs to it and realignments over the years have made their mark. Yet, the break wall remains a steadfast fixture of our harbour.

The Great Wall

China has its Great Wall and so does Thunder Bay. Both walls were built for protection and each wall was a feat of engineering in its day. China’s wall spans a huge nation standing tall as a monument to a world of centuries past. Standing proudly from the lake bottom with only its top showing like the tip of an iceberg, the Great Wall of Thunder Bay still performs the task for which it was constructed. It protects the harbour admirably and will for decades to come. Our Great Wall is an integral part of what made our harbour a destination for the world. It stands tall as a monument to the foresight and fortitude of the founders of the Great Port of Thunder Bay.