In today’s Canada, we enjoy good railway, road and aviation systems that traverse the country. We can ride the rail, drive or fly to almost any destination we wish. Just 100 years ago, things were quite different. The national railway linking east coast to west was still new. There was no TransCanada highway spanning the continent, and aviation was in its infancy. As much as the building of the Canadian Pacific railway is credited with forging this nation, bush pilots were responsible for opening up and maintaining the communities throughout this country that were isolated by the rugged terrain of this great land. To these isolated and often sparsely populated communities, bush pilots were a life line. Trappers, prospectors, missionaries, mountaineers, sportsmen and entrepreneurs in these places all relied on the bush pilot.

Bush flying began in Canada after World War I when there was a glut of surplus warplanes and service-trained pilots who found a new use for their skills providing air service to remote areas. The “bush” in bush pilot originally described the scrublands of South Africa. Eventually, the word bush was used to depict everything from wind-swept tundra and northern boreal forests to the sand dunes of the Sahara. These intrepid aviators flew second hand planes that had been damaged, repaired and patched so many times that, as one pilot admitted, they were little more than a collection of spare parts. They flew over ice-covered mountains, barren tundra, dense forests and arid deserts to bring food, medicine, mail and emergency aid to communities that could only be reached by air. Al Cheesman, Orville Wieben, Punch Dickins, John Peacock, Elmer Ruddick, Stan Wagner, Wop May, Hellick Kenyan and Duke Schiller are some of the bush pilots who flew all over Northwestern Ontario. From Nakina, Hudson, Rossport, Armstrong, Sioux Lookout, Red Lake, Big Trout Lake, the twin cities and beyond, these pilots were vital. These pilots and their planes brought isolated communities into the 20th century. They could fly over rugged terrain in hours what would take days or weeks to traverse on the ground.

“They must be crazy”

To service these isolated communities, bush pilots had to teach themselves flying techniques unthinkable to pilots from the more “civilized” world. Since there were few airports available, they taught themselves to land planes on sand bars in the middle of rivers, landing strips carved out of dense forest, arctic ice flows and on narrow strips perched precariously on mountain sides. At times, they flew without a radio or weather reports over unmapped mountains in the worst weather. With a ceiling of less than 200 feet and visibility less than a quarter of a mile, when all other planes were grounded, bush pilots would come in for a landing. “They must be crazy,” an air traffic controller remarked once. Bush pilots thought nothing of it.

Bush pilots performed incredibly dangerous flying making them larger than life folk heroes to the people of the region they served. The stories of their courage, skill and often reckless and risky exploits expanded beyond the area where they flew. Newspapers of the 1920s and 30s covered their triumphs and avidly followed the massive aerial manhunts when one of them was forced down in some unmapped wilderness. The newspaper stories and heart-stopping tales fostered a dramatic lore of the bush pilot’s flying skill and dogged determination.

World War II brought with it huge advances in aviation which served to expand bush flying. Pilots could now use abandoned air force airstrips. Technological improvements to aircraft meant more sophisticated, reliable planes, communications equipment and navigational aids. With all the advances in aviation came better snow removal equipment too which meant that heavier aircraft than the more nimble bush plane could land at these airstrips year round. This led to a boom in aviation in Canada after the war. The boom would, in turn, bring about the disappearance of many small bush operations and the development of others into scheduled air services.

The Flying Alderman

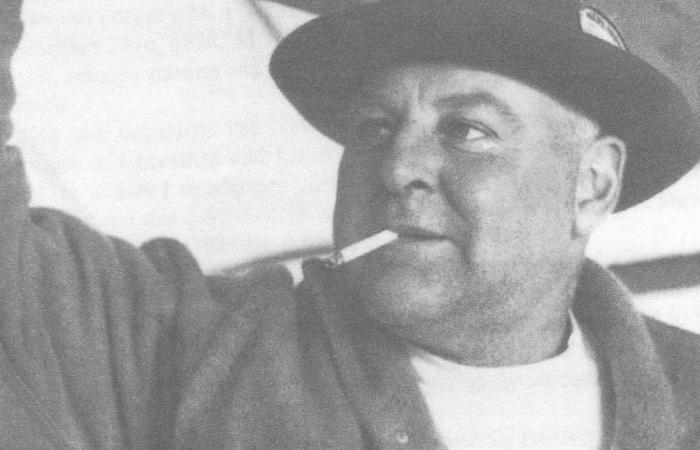

Silas Alward “Al” Cheesman, renowned bush pilot of the Lakehead, was born in St. John, NB. Al began his career as an airplane mechanic for Ontario Provincial Airways based in Sault Ste Marie in 1925. When fellow bush pilot H.A. “Doc” Oakes formed Western Canada Airways, he hired Al as chief mechanic. Cheesman joined Oakes on Sir Hubert Wilkins expedition to the Antarctic in 1929-30 where he became the first Canadian to fly in the Antarctic, had an island named after him and gained international acclaim for his skills in cold weather flying. But Al’s aviation career didn’t really begin until he settled in Port Arthur in 1931 working for Pigeon Lumber Company. In 1933 he bought the air division of his employer and started his own Explorer Airways. His colourful, flamboyant personality made him very popular with the citizens of Port Arthur. He was elected an Alderman of Port Arthur serving one term from 1936-38 and was known as “The Flying Alderman.” A flying accident in Port Arthur harbour totaled Al Cheesman’s plane. He emerged from the wreckage unharmed, but that signaled the end of Explorer Airways. Al left the Lakehead to serve in the RCAF for four years. When he returned to Port Arthur in 1945, he worked for Thunder Bay Airlines, then Can-Car and finally Orville Wieben’s Superior Airways.

During his career, as well as flying workers and equipment to remote job sites, or sportsmen to camps, Al Cheesman flew mercy missions. For one such mission, Al had to fly, at dusk, a doctor west to see a seriously ill woman. Al could just make out the harbour as they landed in the fading light. He expected to be flying back to Port Arthur with the doctor and ill woman the next morning. At midnight, the doctor informed Al that his patient had to go to the hospital right away or she would die. Al decided to do what is contrary to all the rules of aviation, which was, to take off at night, moonless as it was, with no idea of where the rocks, shoals or islands were in the dark water. He taxied out to where he figured they had enough room to take off, closed his eyes and prayed hard, “Dear God, please be my co-pilot.” Then he gunned the engine to full throttle, the plane surged forward and they became airborne just barely clearing the trees. When they got back to the Port Arthur harbour, Al couldn’t see where to land in the blackened water. So he kept buzzing the CLE until someone realized his predicament. Tug boats turned on their powerful headlights to light up the harbour enough so they could land. When they had taxied to the shore, the woman was rushed to hospital and she survived. Al’s mission inspired the book and movie “God Is My Co-Pilot.”

Sadly, Al Cheesman’s adventurous life caught up with him. In December of 1956, Al suffered a heart attack. He

was treated in Winnipeg, but upon returning to Port Arthur he developed pneumonia and died in McKellar

Hospital April 2, 1957.